Scientists Revive Ancient Worm , Frozen For Tens of Thousands of Years.

CNN reports that scientists have revived a 46,000-year-old worm found frozen in the Siberian permafrost.

.

CNN reports that scientists have revived a 46,000-year-old worm found frozen in the Siberian permafrost.

.

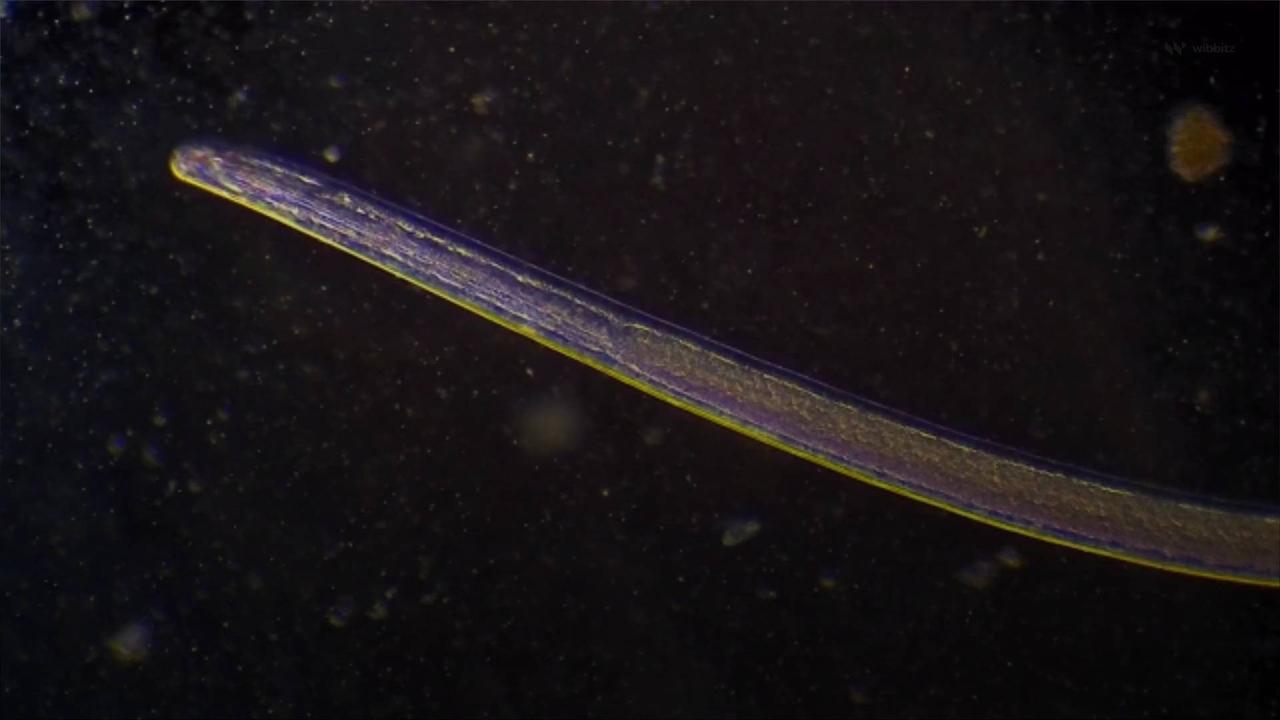

The previously unknown species of roundworm, which lived at a time when wooly mammoths still roamed the Earth, survived far below the surface of the permafrost.

The previously unknown species of roundworm, which lived at a time when wooly mammoths still roamed the Earth, survived far below the surface of the permafrost.

According to Teymuras Kurzchalia, the worm survived in a dormant state known as cryptobiosis.

.

Kurzchalia, a professor emeritus at the Max Planck Institute of Molecular Cell Biology and Genetics, says the crytobiotic state is "between life and death.".

Cryptobiosis allows an organism to survive the complete absence of water or oxygen and even withstand extreme heat or freezing temperatures.

According to Kurzchalia, previous research into cryptobiosis saw organisms revived after decades rather than millennia.

CNN reports that radiocarbon analysis established that the deposits where the worms were found had last been thawed between 45,839 and 47,769 years ago.

To see that the same biochemical pathway is used in a species which is 200, 300 million years away, that’s really striking, Philipp Schiffer, Research group leader of the Institute of Zoology at the University of Cologne, via CNN.

It means that some processes in evolution are deeply conserved, Philipp Schiffer, Research group leader of the Institute of Zoology at the University of Cologne, via CNN.

By looking at and analyzing these animals, we can maybe inform conservation biology, or maybe even develop efforts to protect other species, or at least learn what to do to protect them in these extreme conditions that we have now, Philipp Schiffer, Research group leader of the Institute of Zoology at the University of Cologne, via CNN